If you could see what they see: Window views of Philly employees installed at City Hall

The photo exhibit aims to humanize public sector work, which is often seen as a faceless bureaucratic wall.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

“I love watching the protests through my window,” said one anonymous Philadelphia city employee.

“Especially seeing kids of color involved — that’s my favorite thing in the world,” the employee said. “There’s not a lot of Hispanic kids involved in anything. I feel we’re very excluded from a lot. But when I see kids that are Hispanic or Black involved in government, wanting to make a difference, it’s really amazing.”

The unnamed city worker is included in “Civic Views,” a photography exhibit of office windows where city employees work, showing what they see when they look outside. The project of Mural Arts Philadelphia features 15 life-size photos cropped to the actual dimensions of the windows that are now on display in the courtyard at Philadelphia City Hall.

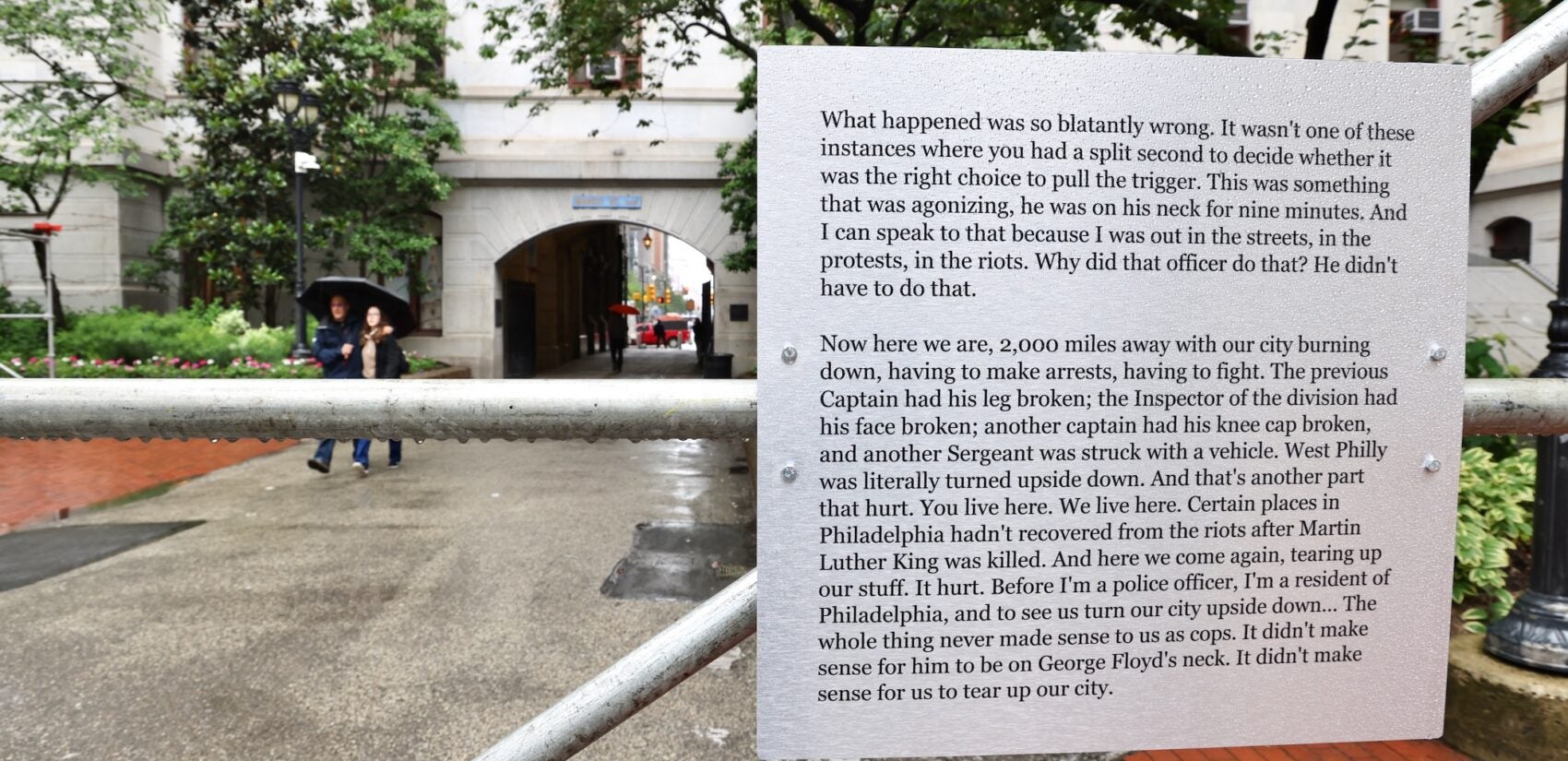

The images are encased in weather-sealed plexiglass and hung on scaffolding, accompanied by excerpts from interviews that photographer Emilio Martínez Poppe conducted with dozens of city employees from 20 different departments.

A municipal employee himself — he studied urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania and now works in New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs — Poppe wanted to humanize public sector work, which he says many people regard as a faceless bureaucratic wall or, in the case of the President Donald Trump’s termination of government agencies and their staffs, as a burden to be eliminated.

“Thinking about a full-scale assault on the public sector at the federal level and then here thinking about it at the municipal level, what does it mean to lose our public services that help us come together collectively to imagine who we are,” he said. “That’s what the public sector offers us. That’s the promise.”

Poppe was initially inspired by the first known photo to be taken in the United States. In 1839, Joseph Saxton, an employee at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, then at Chestnut and Juniper streets, took a daguerreotype out his office window using a primitive camera he made out of a cigar box.

More than 180 years later, we can still see what Saxton saw every day: the cupola of Central High School and a portion of the State Armory building.

Poppe started taking photos for “Civic Views” in 2023, a time of great upheaval in the workforce, and in the public sector in particular, with pandemic shutdowns and street protests.

One of the interview subjects who works in the police department said he was disheartened by George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020, and equally so by the subsequent protests in Philadelphia that caused widespread destruction.

“Before I’m a police officer, I’m a resident of Philadelphia, and to see us turn our city upside down … The whole thing never made sense to us as cops,” said the unidentified police employee. “It didn’t make sense for him to be on George Floyd’s neck. It didn’t make sense for us to tear up our city.”

The worldview from city employee windows can vary greatly. Some vistas include lots of sky and enviable views of the city skyline. Others only look out on a brick wall. Some of the photos Poppe took feature personal objects on the windowsill: a plant, a small collection of PEZ candy dispensers, a tube of lip balm.

“We want people to have a re-engagement with the public sector,” said curator Jameson Paige. “These are people. They’re working for us, but they’re also part of the city. They also get services from the city. To just shake off some of the abstraction.”

The interviewees were promised that their names and departments would not be identified, to encourage them to speak more freely than they might otherwise. Paige noted that the interviews were remarkably consistent in the subjects’ belief in the altruistic ideals of public sector work, even if the day-to-day challenges can be a grind.

“It’s a pretty thankless job. I can probably count on one hand the amount of people who have said, ‘I know that I wasn’t the nicest person to you, but you changed my life for the better,’” said one unnamed subject. “But we don’t really do it for that. If I was looking for gratitude, I’d be in a different line of business. We do it because we know it’s the right thing to do.”

Poppe hung the photos on scaffolding because, for one, so much of Philadelphia seems to be behind scaffolding as the city experiences a building boom. Metaphorically, scaffolding is temporary, something erected with the expectation of improving a structure, then disassembled. Poppe sees the city, generally, and its workforce to be an ongoing work in progress.

“The institutions may seem like monolithic entities that are unmovable, but in fact they are people,” he said. “They are made up by people every day trying to make change in different capacities. This project aims to collect a series of diverse voices to think about what it means to struggle towards progressive change.”

Poppe took more pictures and interviewed more people than are seen in “Civic Views.” He hopes to expand the exhibition in a book. In the short term, after “Civic Views” comes down in June, a smaller iteration of the exhibition will be installed across the street at the Municipal Services Building.

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.